Who Is The Creator?

Artists throughout history have collaborated with and learned from other artists, have been directly or indirectly guided by them and have even employed artists with a ‘very particular set of skills’ to complete work for them. Often, though not always, these creative relationships were born out of necessity.

It was after the making of my NFT animation ‘Who is the Creator’ that I decided to write this article to delve deeper into the history of art collaboration and the practice of outsourcing work to other specialists which some artists employ to help them realise their creative visions.

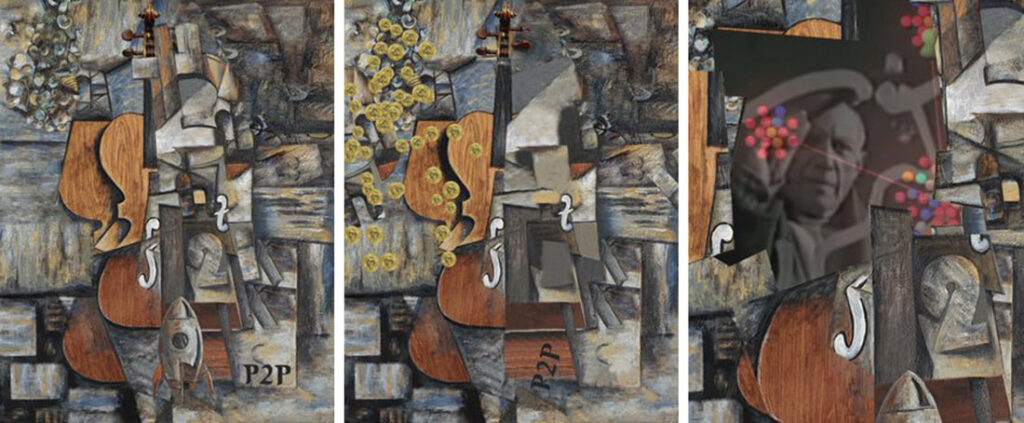

‘Who is the Creator?’ is a digital artwork conceived from my physical oil painting ‘Violin, Grapes and Bitcoin’, which in turn is a reinterpretation of Picasso’s analytical cubism masterpiece ‘Violin and Grapes’. I titled this digital piece with the notion of creative partnerships at the forefront of my thoughts. To underscore the significance of Picasso’s input I included in the digital work the video clip of him appropriately painting a bull while the upper layers of paint perpetually construct and fracture into cubism-like, geometric planes.

Grapes metamorphose and multiply into bitcoin that shower down to the ground and a rocket launches and vanishes into the atmosphere. As the painting animates, the grapes/coins and rocket along with the other crypto iconography embedded into it dislodge and activate. More subtle however, is the secondary video underneath; the visualisation of the Bitcoin network accrediting the OG and Creator, Satoshi Nakamoto.

However, the aim of this essay is not so much to discuss the painting but instead to explore in an historical context how creative collaboration as well as the ‘ad hoc’ hiring model employed by artists since the 16th century have been invaluable mechanisms to realise one’s artistic vision. I’ll also discuss how artists in the cryptoart space are benefiting from similar relationships and creative processes albeit updated versions while at the same time I’ll encourage the reader to question from where an artwork truly originates and how much of the end piece is in fact wholly of the artist.

A Fruitful Relationship

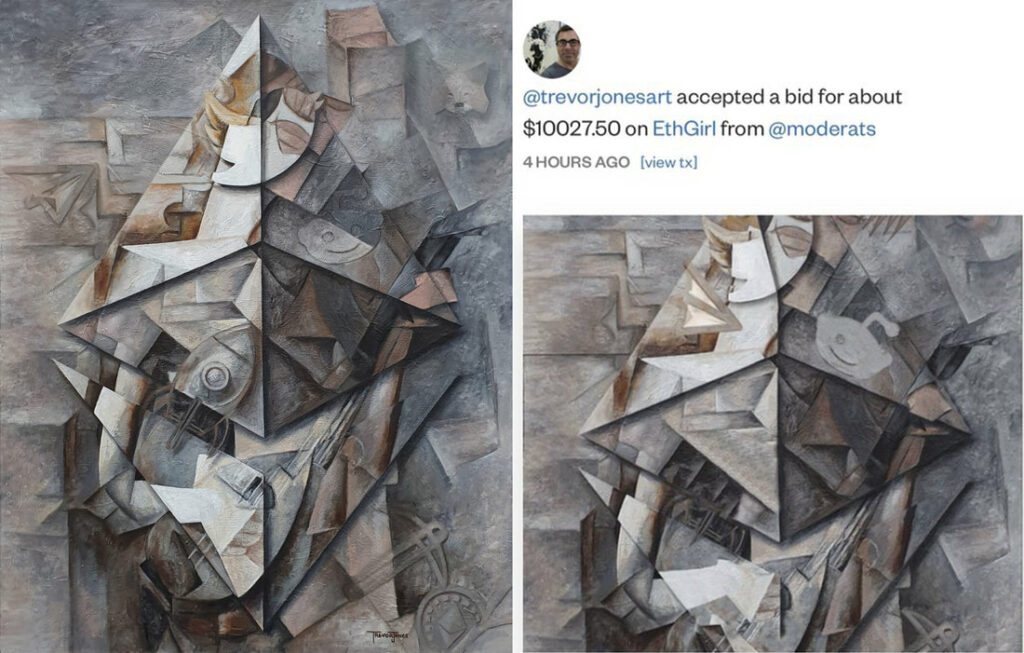

After the hugely successful launch of the EthGirl project with the brilliant @money_allota I was looking forward to working with him again on another piece. Unfortunately, Alotta became the victim of his own success and he’s currently so backed up with other business that it could very well be years before he has the time for a TJones + Alotta reunion. I hope not.

I was disappointed at first but at the same time I saw this as an interesting opportunity. I began thinking about how (and why) artists throughout history have worked together as they adapted to challenges including creative stagnation, supply and demand, or requiring more specialised technical abilities to realise their vision.

This in turn got me thinking about the ubiquitous dual-artist projects appearing in the crypto space right now and how many of these NFT artists are sharing skills, learning from each other and producing exciting works of art that never could have been created as solo projects. It does seem to be a win/win for everyone involved including the collectors who are benefiting from an ever-expanding gallery of quality artwork to enjoy and invest in.

In the Beginning

One could argue that many cave paintings dating back tens of thousands of years are the first examples of artistic collaboration, but I’m not going to talk about these. I’m trying to write an interesting and succinct essay and not a PhD thesis!

So instead, let’s begin with the Renaissance when the Western art world really began rocking it. By the early 1500’s the most skilled artists were running huge workshops taking on apprentices and hiring journeyman artists. The more experienced apprentices would perform various functions with the paintings such as filling in some of the background, painting drapery and possibly even adding in some of the people on larger compositions.

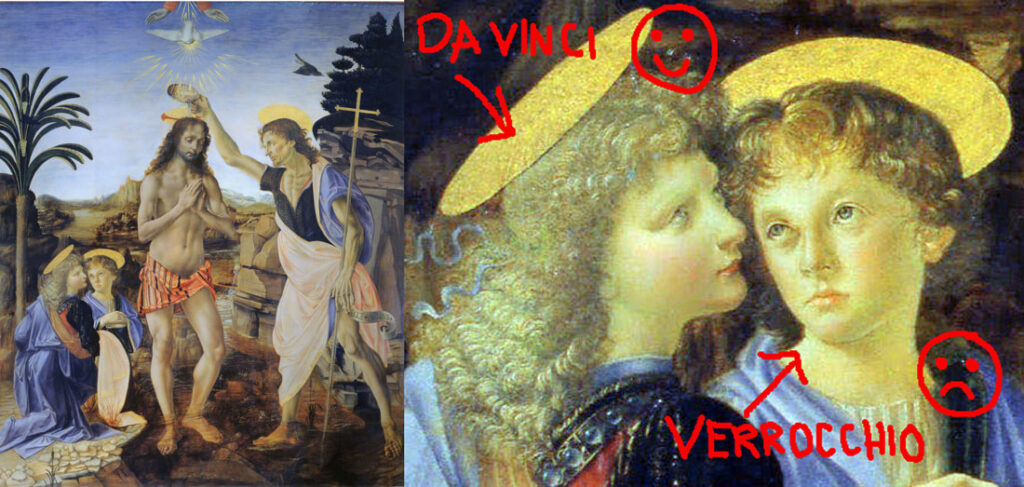

Artists began as apprentices at a very young age and children working at ten years old and even younger was not uncommon. Shhh, child labour!! It was through years of workshop experience under the tutelage of the master that the youngsters were able to gain knowledge and skills and, if talented enough, they were able to eventually become masters in their own right. Even Leonardo da Vinci was a journeyman, working with the famous Verrocchio.

You can see in Verrocchio’s painting, Baptism of Christ (1472), a 20 year old Da Vinci added to part of the landscape and painted one of the angels. According to the Renaissance writer Vasari, Da Vinci’s angel was so impressive that the great Verrocchio decided on the spot to quit painting. I guess having the young protégé Da Vinci as your soon-to-be competition would be pretty soul destroying for anyone.

The workshop model was really ticking along; however, this all began to change by the late 16th century. Why? Well, in part, some of the masters were looking for a little more work/life balance, travel opportunities and more flexibility in their work environment – but a lot of it was down to ego. The master and apprentice workshop model began to decline as a stigma emerged with it being associated with the artisan tradespeople who, in public opinion, lacked any level of sophistication or education.

The great painters, sculptors and architects saw themselves more as creative geniuses than as craftsmen and were looking to raise their status (and their wages) in society. Some things never change, hey? Therefore, they needed to distance themselves from the perception of ‘mere’ craftsmen with their factory-like artwork production.

The exceptionally gifted master artists were able to achieve this elevated status in part by shutting down their workshops, becoming independent i.e. going solo and thereby having more flexibility for travel, better opportunities to network and the possibility to secure large commissions with wealthy patrons in different regions or countries. In a way, they became the first gig workers of the 16th century. Of course, they still needed help on the bigger projects and so they would hire assistants ad hoc when necessary.

The More Things Change The More They Stay The Same

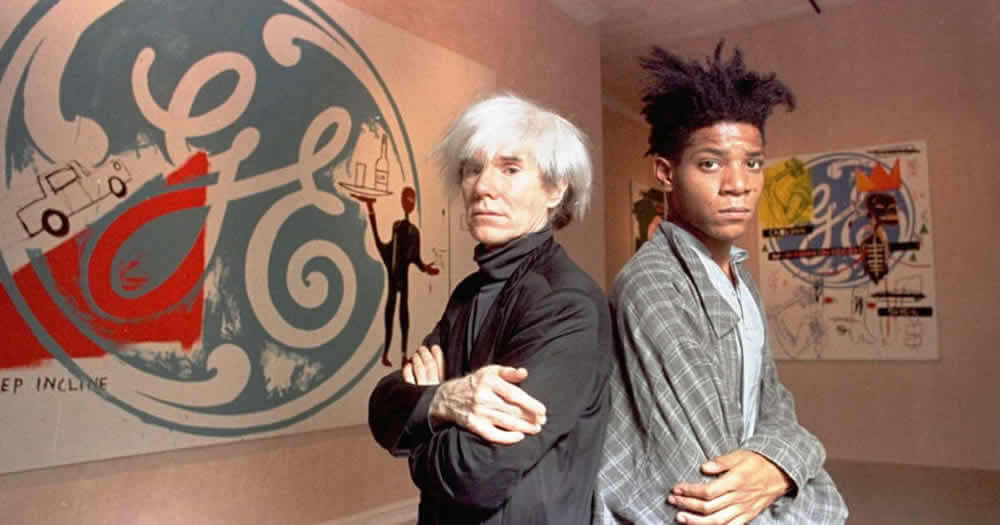

Artist collaborations have played important roles in the creation of some of the world’s most recognisable works of art. A few examples of exceptional partnerships include Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat, Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, and Pablo Picasso and Gjon Mili. And then of course there are the artists whose entire careers have been built on collaboration such as Christo and Jeanne-Claude and Gilbert and George. So, what exactly are the benefits of partnerships and why do so many artists follow this creative route?

Why Collaboration Is The Way to Grow As An Artist

- Collaboration can help introduce your work to a new audience

- There’s the opportunity to promote each other on your respective media channels

- Collaboration can further help you create a brand image around your name

- Collaborations can lead to exceptionally innovative and creative art projects

- Collaborations can promote growth rather than competition

- Collaboration helps you stay connected and to grow with some of the best people the space

Now that I’ve listed a few of the categories of artistic collaboration and the benefits I’d like to draw your attention to how the Renaissance workshop model reinvented itself in the last ½ century.

Employing artists, in particular ones who were more skilled in other areas such as painting trees and foliage or drapery was not unusual throughout the Renaissance but by the mid-20th century the ‘genius artist’ studio/workshop model was being pumped full of steroids, taking on an entirely new and almost unrecognisable appearance.

Andy Warhol was one of the masterminds behind this shift citing the Henry Ford production line ethos and the car maker’s success and market domination to help legitimise the artist’s screen printing mass production techniques. Skip ahead a few more decades and artists such as Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst have added rocket fuel and uranium to take Warhol’s studio concept to an even greater and more ostentatious level with Koons’ New York ‘factory’ having even been likened to an Apple plant.

Both Koons and Hirst each, quite literally, have hundreds of artist employees and skilled professionals creating their art pieces, often entirely from start to finish. Hirst admitted he doesn’t even see many of the artworks being worked on in his studios until they’re completed and only at that point he decides if they ‘pass the grade’ to be exhibited.

But Is It Art?

I’m not the biggest fan of this ‘artist as designer only’ phenomenon. Perhaps I’ll change my mind in the future as my own career and creative practice progresses because, in my opinion, it’s imperative that an artist continually questions everything including their prejudices, pushes their boundaries and explores new ways of working.

David Hockney, one of my favourite artists, has always experimented with his working methods, however; he is still quite sceptical of the ‘designer only’ practice. In a not so subtle jab at Hirst, Hockney’s 2012 exhibition poster stated, “All the works here were made by the artist himself, personally.” Hockney explained in an interview, “I used to point out at art school, you can teach the craft, it’s the poetry you can’t teach. But now they try to teach the poetry and not the craft.This debate will likely always be a topic of contention between artists, art lovers and critics alike but I can’t imagine the practice ever becoming obsolete. At any rate, it’s not difficult to argue that the studios of Warhol, Koons and Hirst are a natural progression from the Renaissance workshop model and, in fact, many of the most established artists of the past century have in some way shape or form experimented with working methods that weren’t 100% entirely ‘of their hand’. Picasso was another artist who benefited greatly from various types of (often lopsided) collaborative relationships. Don’t even mention Braque!

In fact, although Picasso has been credited with making over 100,000 prints, 10,000 photographs and 3,500 ceramic pieces throughout his career, the bulk of the ‘grunt work’ was carried out by specialists, master printmakers and ceramicists etc. I guess to be fair, one can’t blame Picasso for this practice as it was also common knowledge that his use of technical professionals was driven by his eagerness to experiment, which he did even up until his final years.

No matter where one sits in this conversation around the question, “How much of the ‘hand of the artist’ is essential to actually make it their work of art?”, one can’t dispute the success of artists like Hirst and Koons. Both of these artists have taken the notion of ‘The Conceptual’ to the next level and have done exceptionally well because of this.

My intention in writing this essay is not meant to criticise the working methods or tools used by other artists, it is only an attempt to be a (very tiny) historical breakdown of a few of the types of collaborative models and working relationships that have helped to produce some of the most famous artists and artwork in history. Of course, we all have our own opinions as to what we think makes a great work of art and the processes involved in its creation will inevitably play a role in how we feel about it.

And finally, back to ‘Who is the Creator?’

When I discovered that I wouldn’t be able to work with Alotta on my second NFT I decided to take the ‘hired gun’ approach i.e. the Renaissance ad hoc specialist. I found a talented and experienced digital artist/animator who was able to help me realise my artistic vision and I have to say, although it took some back and forth conversation, the result is everything I’d envisioned. Moreover, employing someone else to work on other elements of my final pieces gives me more time to focus on what I do best, paint. ‘Who is the Creator’ is of course hugely influenced by Picasso but in other ways Satoshi Nakamoto made his own valuable contribution to the work. I also learned from Alotta through our EthGirl collaboration, which inevitable shaped some of my thought processes for this artwork.

I think that this is one of the great benefits of collaboration: through interaction with other creatives we push our boundaries as we learn and, in the process, we discover new and exciting creative possibilities. We solve problems through partnerships and consequently develop an artistic vision of a physical (or digital) work of art that would never have materialised otherwise. Through all the different kinds of artist collaborations knowledge and experience are internalised, and new skill sets are carried forward in one’s future work.

One could quite easily argue that many of my past tutors, mentors and even the influential artists I’ve admired and studied over the years have all, in some way, played a part in the making of this piece.

In Summary

Who then really IS the creator of a work of art? Who is the Creator when two artists collaborate? Who is the Creator when an artist hires an ‘ad hoc’ specialist to develop the final piece or, as in Koon’s or Hirst’s case, hire people to produce the entire artwork from concept to completion?

Who is the Creator when an artist uses an app to produce an artwork from one of their own original pieces or when an artist takes two or more stock images and inputs them into the same app to create something new? These last questions fascinate me. In my mind, there are definitely pros and cons to experimenting with and creating digital works with the likes of artbreeder, photomosh, and the assortments of glitch apps available. However, I think relying on apps such as these can very quickly lead one down a slippery slope as the work can turn into ‘all show and no go’ i.e. it looks super cool but there’s not really any substance or depth to it.

Below are two of my experiments with Artbreeder, which is a website that lets you combine images using machine learning. I uploaded a Michelangelo figure in the left image and transformed it with the various setting options and in the right image I combined one of my own abstract paintings with an Artbreeder stock portrait image.

One could argue that these new and exciting digital tools are in fact comparable to the traditional collaborative partnerships between two artists or to the hiring of uniquely talented specialists. I’d contend that the quality of the new NFT artworks being produced will rest on how and why these digital tools are being used by the artist, which will subsequently determine how the finished work will be defined by others as exceptional or forgettable – i.e. art academics, critics and writers. Regardless, I’m certain that future art historians will do their best to unpack many of the NFT artworks being produced today as they write about the origins of the cryptoart scene.In conclusion, as far as I’m aware ‘Who’s the Creator’ is one of the first (possibly the first?) examples of an artist employing the Renaissance ‘ad hoc’ model to create an NFT artwork by hiring a trained specialist. I’m looking very forward to how this new art world develops in the coming months and years and how collaborations (with other artists and/or technology) will continue to add to and influence this new frontier.

“You have to know the past to understand the present.” ~ Carl Sagan

Update: Interestingly, it was about 6 months after posting this on my website and tweeting it that it was ‘discovered’ that I hired a professional to produce my animations for NFTs. This was further discussed (and challenged) on Twitter, becoming a point of contention for many. I enjoyed the debate and in turn this led me to contact the great Jose Delbo for a collaboration artwork that would (intentionally) spark even more controversy. Never shy away from a challenge.

Find out about the artwork and NFTs I created with Jose Delbo.

To end, here are a few examples of my favourite NFT artist collaborations to date.

@hackatao and @oficinastk – Crazy Diamond [End-2019]

@money_alotta and @jivdontexist – Saint Andreas

@Coldie and @Xcopy – DystoPunk

@oficinastk, @MattiaC and @ilan_katin – Islands and Strange ShoresIf you have any questions or would like to add your own favourite artist partnerships feel free to comment below.

Resources:

Georges Braque, The Father Of Cubism; Subarna Ganguly

Damien Hirst’s work is an insult to craftsmen; The Telegraph

The Evolution of the Artist’s Studio; Ian Wallace

Artists and the Workshop in 16th-century Florence; Louis Waldman

The World of Leonardo: 1452-1519; Robert Wallace

Why Collaboration Is The Way to Grow As An Artist; Shreya Dalela