Bitcoin Bull – an Essay

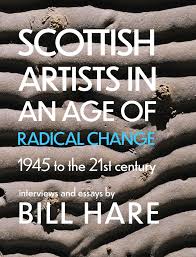

Bill Hare is a lecturer and Honorary Fellow in Scottish Art History at the University of Edinburgh and the author of Scottish Artists in an Age of Radical Change, Contemporary Painting in Scotland, Divided Selves, Facing the Nation and more. His books have been a staple of every Scottish art history major over the last three decades.

More here about the Bitcoin Bull painting and the record breaking Nifty Gateway auction.

“It is pictures, rather than propositions, metaphors, rather than statements, which determine most of our philosophical convictions.”

Richard Rorty

How can we get the most out of our critical engagement and aesthetic appreciation from a complex painting such as Trevor Jones’s Bitcoin Bull? We might take the advice of the contemporary philosopher Richard Rorty, who has suggested that the approach to his own discipline should radically change from being predominately academic, to becoming much more conversational.

Of course, works of art do appear to be mute, but surprisingly, they can be encouraged to open up and “speak” to us, if we are able to understand and connect with them through their particular pictorial means of communication. The best way to spark this creative conversation is to ask relevant and provocative questions. The first and probably the most fundamental and crucial one is, “why does the painting- in this case the Bitcoin Bull look the way it does?” What has the artist brought to bear-both in iconography and technique-to give this picture its distinctive image?

In the past that initial question would have been much easier to procure an agreed answer when most of Western art spoke in the memetic language of visual resemblance. If we go back to the beginnings of Western art and the ancient Greeks for instance, we find Socrates likening the artist to a person carrying a mirror around desperately trying to capture the fleeting appearances of the world and the things in it. That kind of reflected memetic naturalism was so admired that it was said that the best of the Greek painters could depict a bunch of grapes so convincingly that birds would come down and mistakenly try to pick them! (I doubt very much that even a myopic sparrow would be fooled by the depiction of the fruit in Jones’ cubist-like painting.)

That mode of visual naturalism remained the dominant language of Western art right up to the end of the 19th century- with its final great triumph in Impressionism. Within less than a generation however, that long serving means of pictorial communication was seriously challenged by the revolutionary invention of Cubism by Braque and Picasso. Of course, the vast majority found Cubism both baffling and incomprehensible, not only because cubist pictures looked radically different, but more crucially, because they “spoke’ in a fundamentally different language of visual communication which was not based on optical resemblance, but visual metaphor.

Despite its radical innovative impact, the metaphoric approach to picture making of Cubism did not completely take over 20th century modern art, but what it did do was to offer ambitious progressive artists the possibility of a polyphonic, multilingual approach to the aims of their art. This hybrid of different pictorial styles is most famously seen in the wide-ranging protean career of Picasso himself and Jones has taken up this modernist challenge within a postmodern context.

Painted a century after the invention of Cubism, the Bitcoin Bull could never be a bona fide cubist picture, but it is a very knowledgeable and witty contemporary stylistic re-description and re-interpretation of that mode of pictorial representation. That said, it does share one of the very important characteristics with its modern source. Cubism was the first pictorial innovation that rejected the submissive copyist approach of memetic naturalism and radically substituted an active, constructive method of picture-making in its place. Jones’ painting does the same. This has crucial implications for the viewer as well, who now, when confronted with such a work can no longer retain a passive contemplative attitude but is obliged to become a pro-active reader of the artist’s pictorial signage, out of which a speculative meaning might be constructed.

With ingenuity and wit Jones has re-worked his own take on this metaphorical mode of visual communication in his fascinating Bitcoin Bull. Playing with Picasso’s eponymous bull image, his fragmented still life and his famous use of collaged pieces of newspaper in the form of ‘journ” (“jou” in French means play, or game), Jones has turned his own pictorial iconography into an intriguing and entertaining puzzle of visual metaphor and puns.

Furthermore, as Picasso’s cubist pictures could discourse on the great issues of his era, especially through collaged newspaper articles, the Bitcoin Bull similarly makes a range of pictorial references toward our present world of multi-media communication and currency exchange through the discreet incorporation of the logos of twitter, Bitcoin, Gemini, Niftygateway etc. As Richard Rorty argues in his writings, our “picture” of the world is never stable, but constantly subject to an endless, ever-changing stream of descriptions and re-descriptions. Thus, the art of Trevor Jones fits into this pattern with his eclectic re-visiting and re-working of the inheritance of Modernism and-particularly the Picasso’s relevant context of contemporary multi-media hieroglyphics.

As has been claimed, our picture of the world is not fixed, is never fixed, nor is its meaning. In the area of critical interpretation of art, it is not the artist- the artistic producer, but the viewer-the cultural consumer – who plays the crucially influential role as the interpreter of meaning which will of course vary from viewer to viewer. For instance, my take on the Bitcoin Bull is very much conditioned and formed by my training as an art historian. On the other hand, because the painting discourses on the complex relationship between art and money, an art dealer might look at the same picture from a very different angle. That particular viewer is therefore more likely to place the work, not in an art historical context, but within the workings of the contemporary art market. Interestingly this does raise the contentious issue of the relationship between artistic quality and market value, which has dogged art practice and debate since the 17th century. For example, when Rembrandt painted his now celebrated Aristotle with the Bust of Homer in 1653, he was on the verge of bankruptcy and destitution and yet that same painting was bought by The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1961 for a then world record price of 2.3 million dollars, and is now one of the most popular attractions in its magnificent collection.

Whether we like it or not, the extravagant excesses of the art market can undoubtedly be a challenge to how we look and judge the meaning and value of works of art. The Bitcoin Bull takes on that challenge, by confronting the viewer with an absorbing and stimulating pictorial debate, concerning the complex and shifting relationship between the demands of art and its history, and the conditions for critical recognition, popular acclaim and monetary success in the contemporary art world.

Bill Hare