Sacred And Profane

THE BITCOIN ANGEL

“Satire is a lesson; parody is a game” ~ Vladimir Nabokov

The Bitcoin Angel oil painting by Trevor Jones is a very striking example of a notable and recurring feature of modern and contemporary art. Right from the outset of modern art in the middle of the 19th century many avant-garde artists wished to create within their work, a dialectical tension between the inherited tradition of art history and the innovative agenda of Modernism. This was in order to set-up and expand a creative dialogue between the art of the past and theirs of present. For instance, we can find this eclectic strategy within the paintings of Manet, such as Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe and Olympia. In such early masterpieces of modern painting the “Father of Modern Art” wittily references Old Masters such as Raphael and Titian in order to discuss pictorially such issues as academic nudity and mundane nakedness, eternal beauty and passing fashion within a modern life milieu. Unfortunately, in these marvelous pictorial parodies, both the seriousness and humor of Manet’s intent were lost on his initial hostile public; but thankfully not on the swelling avant-garde movement that followed on from him.

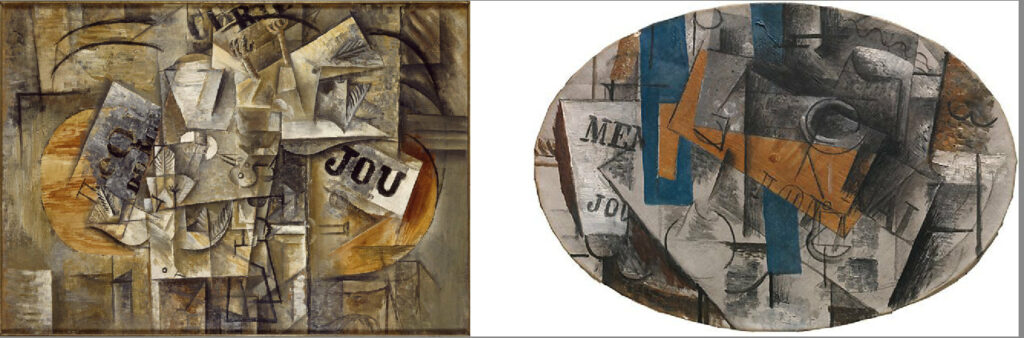

By the time Cubism emerged at the beginning of the 20th-century the idea of parodying the academic conventions of the artistic tradition was built into the modernist creative strategy. In their radical assault on pictorial memetic illusionism Braque and Picasso for example, would often introduce surrogate text into their collaged still lives. For instance, they would frequently include the word “jou”(the French term for having fun) to express the concept of playfulness. This use of parody, often with much more vicious and subversive intent, was soon taken up by the Dadaists and Surrealists who used it as one of their main assaults on bourgeois culture and its conventions. This recurring strategy of parody in modern art has furthermore continued right through to our postmodern era, in the work of such artists as Andy Warhol, Roy Lichenstein and more recently with Jeff Koons – although now parody can easily come close to mere pastiche.

As can be seen from his work, Trevor Jones is certainly a highly educated painter who is well versed in the history of art. Evidence for this is found in the way his painting frequently engages with old and modern masters such as Picasso, and here with his The Bitcoin Angel, the 17th century Italian sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini. With his keen knowledge of, and deep respect for, his art historical sources, Jones never indulges in cheap pastiche, but, like Manet and Picasso before him, aims to stimulate a meaningful dialogue between the art of the past and our present historical situation.

Bernini’s The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa is a thought-provoking art historical source for an artist like Jones to visit and re-present for his contemporary audience. It is of course, one of Bernini’s most celebrated works and has become an iconic example of 17th century baroque art. Bernini was regarded and lauded as one of the most important propagandists for the Roman Catholic counter-reformation. As can be seen in most of his commissioned work for the Church and its ecclesiastical princes, Bernini’s spectacular art – whether in sculpture or architecture – invariably sets out to sweep up the spectator in a great wave of emotional drama and high theatricality.

This distinctive approach can immediately be discerned in the multi-faceted The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa that Bernini created for the Cornaro Family chapel in Sta Maria della Vittoria, Rome. Here the baroque sculptor, to do full justice to the saint’s visionary ecstatic experience, pulls out all the stops with highly agitated draperies, celestial beams of light, swooning expressions, and demonstrative gestures – all held together by the miraculous illusionism of suspended animation. From the perspective of the 21st century our contemporary artist has chosen to enter a very different world of baroque excess and evangelical fervour.

Wisely, Jones does not overelaborate his intervention into Bernini’s masterpiece. Translating the three-dimensionality of the highly ornate sculptural installation into two-dimensional painting, Jones is obliged to reduce its scale to the size of his canvas and skillfully turn its free-standing figures and accompanying props into a single unified image. This he carries out with superb painterly skill, translating sculptural marble and metal into pictorial texture and pigment. The only major change that Jones makes to Bernini’s original concept is the placement of the Bitcoin logo over the sculptor’s backdrop of gilded rods.

Yet, while this does not greatly alter the compositional format of Bernini’s work, it does of course, radically change and challenge its religious character and ideological significance. Whereas Bernini wishes to elevate the lower terrestrial domain, as exemplified by the floating rock on which St Teresa lies, to the celestial sublime of the golden rays above her, Jones’ intervention reverses this mystical transcendence. Thus, in The Bitcoin Angel heavenly light is now provocatively turned into earthly gold.

Whereas pastiche rarely takes its subject, or even itself, very seriously, parody, on the other hand, is not only motivated by serious intentions, but is concerned to have a provocative impact on its intended audience. With The Bitcoin Angel Jones raises a controversial issue that has repeatedly plagued art over the centuries – the complex relationship between the artistic and the monetary, the aesthetic and the mercenary. Many, especially those of an aesthete’s disposition, wish to see them kept well apart to avoid contamination. Unfortunately for those advocating this cultural apartheid, art and money have always been drawn to each other in one way or another – in fact, they do not seem to be able to exist without each other.

In The Bitcoin Angel Jones brings the spiritual and ethereal realm of Bernini’s Saint Teresa into the domain of the material and moneyed world of the 21st century. With his own particular response to Baudelaire’s injunction that modern art should be a meeting of the “eternal and the transitory”, Jones has produced a complex hybrid work of art in which the mystical and the mundane, the sacred and the profane, the historical and the contemporary, the sculptural and the pictorial – and to blur the Nabokovian distinction – satire and paradox are all brought together in a fascinating and thought-provoking encounter.

Bill Hare